Photograph:

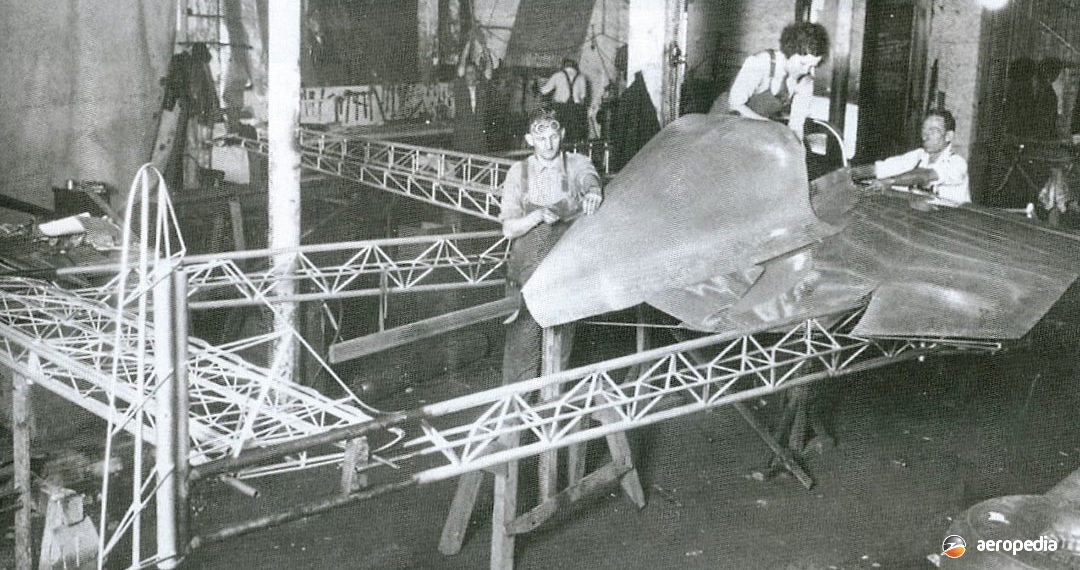

The Centenary Racer whilst under construction at Ryde, NSW (Frank Walters collection)

Country of origin:

Australia

Description:

Two-seat long-distance racing aircraft

Power Plant:

Two 112 kw (150 hp) Harkness Hornet four-cylinder in-line liquid-cooled engines

Specifications:

- Wingspan: 10.05 m (33 ft)

- Mean chord: 1.46 m (4 ft 8 in)

- Length: 6.97 m (22 ft 9 in)

- Wing area: 17.46 m² (188 sq ft)

- Performance estimates without variable pitch propellers

- Max speed at sea level: 322 km/h (200 mph)

- Cruising speed: 290 km/h (180 mph)

- Stalling speed: 116 km/h (72 mph)

- Stalling speed flaps down: 100 km/h (62 mph)

- Initial rate of climb: 244 m/min (800 ft/min)

- Service ceiling: 4,755 m (15,600 ft)

- Absolute ceiling: 5,486 m (18,000 ft)

- Empty weight: 898 kg (1,979 lb)

- Loaded weight: 1,486 kg (3,275 lb)

History:

Following the announcement of plans for the 1934 England to Australia air race sponsored by Sir Macpherson Robertson, an Australian design team comprising L J R Jones, T D J Leech and D Saville set about designing and building an aircraft as an entrant in the race. At that time Mr Jones, who had been involved in the design of a number of aircraft in Sydney, NSW up to that time, was a lecturer in aircraft construction at East Sydney Technical College. Mr Leech was a lecturer in civil engineering and aeronautics at Sydney University, and Mr Saville had been a member of the Royal Air Force and had instructed in navigation.

The project commenced in 1933 and in February the following year a committee met to finance the construction of the aircraft. Initial cost of the project was $4,000 (£2,000) and it was proposed to fit two of the then newly developed Harkness Hornet engines which were expected to provide 201 kw (270 hp) at 2,300 rpm. These engines had been built and were undergoing testing at the time. The body formed to organise the project was known as the All-Australian (British) Aeroplane Fund Committee.

A little has been written about the aircraft over the years. Some publications have called it the Harkness & Hillier Monoplane. The engines initially fitted of 112 kw (150 hp) were mounted on their sides inside the wing and drove variable pitch two-blade propellers, were opposite rotating and had carburettors designed and made in Sydney. Radiators for cooling were installed in the wing leading-edges with a header tank installed above each engine, and the oil tanks installed below. Full span ailerons were fitted, as were flaps. Sometimes the aircraft was known as the ‘Speedjob’.

The aircraft was to seat two, be twin-engined, and was of modern design. The engines were faired into the wings, and the aircraft featured twin-booms. It had a retractable undercarriage. Initially the undercarriage was to be fixed but it was changed to hydraulic retraction by a hand pump. Fuel capacity was 545.5 litres (120 Imp gals) in ten tanks, four in each wing and two in the fuselage behind the cockpit.

Initially Mr Saville was to be the pilot and Mr Jones, who did not hold a pilot’s licence, the co-pilot. Later Miss May Bradford was chosen as the co-pilot, she being a licensed commercial pilot and ground engineer who had worked on the construction of the aircraft.

Construction commenced at the end of 1933 in the basement of a shop in Ryde, NSW and for a period the aircraft was referred to as the “Sunny New South Wales”. The public was asked to contribute towards the construction, and it was said that adequate receipt of donations would permit the aircraft to take part in celebrating Empire Day on 24 May 1934 and be able to demonstrate its capabilities. Much support was given to the project, backers including Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith, the Aero Club of New South Wales, the Australian branch of the Royal Aeronautical Society, and other prominent aviation-minded people, but problems arose due to the Great Depression at that time. Approaches were made to enable the RAAF to investigate the suitability of the design for defence purposes which might lead to possible financial aid, but without success.

Construction proceeded but it was found there were difficulties raising the necessary finance and pleas to the Australian Government did not receive a favourable hearing, it being said that if the Government helped one entrant it would have to help all the entrants. On 9 May 1934 the partially completed aircraft was moved to the Sydney City Grace Brothers department store where construction could continue, the public being able to observe progress when visiting the store. At this stage construction was half-completed, but further money was needed to compete in the race. Further pleas to the Government did not meet with success. On Empire Day 1934 it was announced an anonymous donor had guaranteed the costs of construction. A formal entry was lodged with the Air Race Committee, with Mr Saville as the pilot, and Race No 43 was allotted.

On 31 May 1934 Australian Entry Ltd was set-up to acquire the partially constructed aeroplane for the purpose of entering it in the Melbourne Centenary Air Race. In June that year construction was transferred to the premises of the Tugan Aircraft Company at Mascot, NSW in order to complete it quickly. At this time it was expected to be completed within two months. Trial flights were to be made from Richmond, NSW in late August or early September. The Australian Women’s Weekly magazine then announced it would purchase and sponsor the aircraft.

By mid August the aircraft was said to be two weeks from completion and the team was working “at high pressure”. Testing of the starboard wing revealed it would have to be re-designed as it failed under load tests. However, time was running out. All work ceased near the end of August and on the 30th of the month it was formally announced the aircraft would be withdrawn as the aircraft could not be completed in time. But there were other problems that had emerged. The Harkness Hornet engines were not available in time and two 90 kw (120 hp) Cirrus Hermes IV four-cylinder in-line air-cooled engines driving two-blade wooden propellers were ordered. One arrived but the other inexplicably was off-loaded at Colombo in Ceylon and was not located until after the race. At various stages blame was laid on the failure of early promises of assistance; faulty material being used in construction; and inadequate design time in relation to stress loads which had led to some parts having to be re-designed.

The aircraft was stored for a period in a local engineering workshop, the intention being to complete it at a later time. Lack of finance, and lack of interest in the project, meant the machine was never completed and at the beginning of World War II it was cut up. Some parts are still extant in private collections.

The Centenary Racer was an important part of Australian aviation history. It is tragic it was never completed. The project was never adequately funded at any stage, and the lack of Government support for aircraft design in Australia has not changed. The design was a tribute to Australian ingenuity.